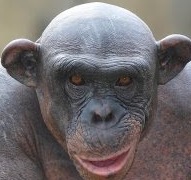

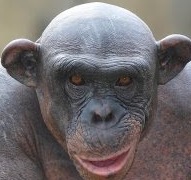

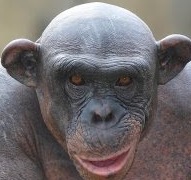

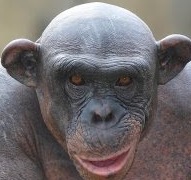

'Every month is a struggle': Two days after learning he had cancer, Tokyo-based English teacher Neil Grainger was told he was HIV-positive. Months later, his employer, Waseda University International Corp., said it would not renew his contract. In the end, Grainger was offered a six-month contract that expired at the end of September. He is now jobless. | SIMON SCOTT

ISSUES | THE FOREIGN ELEMENT

Medical bills mount for ‘fired’ Tokyo English teacher fighting cancer, HIV

Waseda-linked school refuses to renew contract as costs of chemo, operations leave Briton struggling to make ends meet

BY SIMON SCOTT

In the shower one day, long-term Tokyo resident Neil Grainger noticed that the birthmark on his back had changed color. Concerned, he went to the local clinic, but the doctor assured him it was nothing to worry about.

Three or four months later, the mole began to bleed. “I could only wear dark-colored shirts in case it bled during the day,” he says. “If I banged into something, I would get blood on my shirt.”

The 44-year-old Briton then went back to the doctor, and on July 17 last year, after undergoing a series of tests, he was diagnosed with a malignant melanoma.

Then, just a couple of days later, Grainger was dealt another huge blow.

“I got a phone call from the hospital on the Friday and they said, ‘You have got to come back in. We have done some blood tests and have found something else.’ So within three days I found out I was HIV-positive as well. I was diagnosed with cancer on the Wednesday and HIV on the Friday.”

On July 31 he was admitted to hospital and the tumor was removed. Around the same time, he also underwent a plastic-surgery operation where skin taken from his buttocks was grafted onto the area of his back where the cancerous tissue had been.

“I didn’t know it at the time, but [the tumor] was like an iceberg growing underneath. It was one of the largest-ever skin cancers taken from someone in Japan — over 5 cm in depth.”

Grainger says that although he was not aware of it at the time, he ticks many of the boxes for vulnerability to skin cancer.

“I had a birthmark — having a birthmark over a certain size increases one’s risk. Also, I am a Brit living in Japan and not used to the UV here.”

He adds that although he exposed himself to the sun, it was never excessively.

“I have never been a sun freak. That doesn’t mean to say I have never spent days at the beach or the pool, but I am not one of those people who spent a lot of time sun tanning — not at all.”

Although the surgery was successful, Grainger’s troubles were far from over. The cancer had spread to his lymphatic system, and in September he had the lymph nodes on the right side of his body removed.

To prevent the cancer from returning, he also had to undergo an extensive program of immunotherapy. Cancer immunotherapy involves stimulating or strengthening the patient’s immune system in the hope it will reject and destroy tumors. It is a less aggressive form of treatment than chemotherapy, but Grainger still had to endure a harsh regimen of six rounds of multiple painful injections. Each round lasted two weeks and required six jabs in his back and three in his arm daily.

The operations and immunotherapy meant Grainger was forced to take increasing amounts of time off work, which created a whole new raft of problems.

From 2005 until last month, Grainger worked full-time as an English tutor at Waseda University International Corp., a language-school company with more than 200 employees whose main business is supplying additional English courses to Waseda students.

Grainger says that in 2012, despite undergoing two major surgeries, he managed to work about half of August, but was forced to take all of September off. This, he explains, was in part due to a peculiarity in the Japanese health insurance system that discourages workers from taking half-days off sick.

This quirk meant that if he took off half a day, he would get only half a day’s wage, but if he took off a full day, he would be compensated with two-thirds of a day’s pay. Therefore, on days he had to go to the hospital in the morning to receive his injections, he felt compelled to take the full day off, especially considering his mounting medical bills.

Then, in February the following year, just seven months after being diagnosed with cancer and HIV, Grainger was shaken by more bad news: Waseda International “told me they were not going to offer me another contract.”

“At this point, I was actually cancer-free,” Grainger explains, “and I was just having treatment to stop the cancer coming back, so their cutting me off seemed incredibly harsh — basically, they were saying I either stopped having the treatment that was preventing the cancer coming back, or I lost my job.”

Upon hearing the news, Grainger says he was shattered. His job at Waseda was not just some part-time gig to earn a bit of extra pocket money, but his career. And prior to the cancer diagnosis, his future at the company had looked bright. In 2011 he was promoted to senior tutor and took on additional responsibilities outside the classroom, such as teacher training and program administration. According to Grainger, at that time he was promised he would be moved onto a three-year contract once this one-year contract expired.

His work record was also blemish-free, he says. “I have been pretty much a golden boy since I have been there: zero complaints. I was constantly the one who was told I was giving more to the program than anyone else.”

A formal evaluation of Grainger’s work performance was carried out by Waseda International in April 2012 — just three months before he was diagnosed with cancer. On the Employee Evaluation Report, Grainger’s overall work performance is rated as “excellent,” the highest grade.

To quote from the “supervisor evaluation” section of the report: “Neil, you have made a very good transition from Tutor to Senior Tutor. You are very enthusiastic and keen to take on new tasks, which is great. You work well with other Senior Tutors and have already presented a workshop successfully. . . . It has been great to see you volunteer to take on the Lesson Help BBS project. . . . I hope you keep doing a good job as a Senior Tutor next year.”

These comments suggest that Waseda International was not only more than satisfied with Grainger’s work performance, but that they saw him as having an important role to play in the future of the company.

Yet this all changed after Grainger was diagnosed with cancer, he says, and from that point on, management began to look for ways to cut him loose. “They just don’t want people on their books who are a bit of a burden to them,” he says.

According to Grainger, after he launched a campaign to convince the company to change its mind, Waseda International finally relented and decided not to let him go at the end of March when his contract expired. But rather than being given the longer, three-year senior tutor contract he had been expecting, the company put him on a six-month one which, Grainger says, was basically an “enforced leave of absence” and a steppingstone to getting rid of him altogether.

“[Waseda International] fired me, basically,” he says. “So, I wasn’t only fighting for my life, I was fighting for my job as well. Clearly they weren’t on my side. I felt incredibly disillusioned and disappointed, because I had worked so bloody hard for them over the years.”

As the battle to keep his job dragged on, Grainger faced another bombshell: A routine CT scan in April revealed the cancer had returned — and spread.

“On the day I was supposed to get my forms telling my work [that] I was fit to go back and my treatment was finished, the doctors said they had found four tumors in my lungs. That was pretty tough.”

In the diagnosis and treatment of cancer, stages from 0 to IV are commonly used to classify the progression and severity of the illness, with Stage 0 being a noninvasive benign tumor and Stage IV being the final stage, where a tumor has metastasized, or spread, to other organs in the body. With the discovery of the tumors in his lungs, Grainger’s cancer was upgraded from Stage IIIB to IV.

“Up until that point I had been having injections to prevent the cancer coming back,” Grainger says. “From that point onwards, I needed to change to this toxic chemotherapy.”

To date, Grainger has undergone five courses of aggressive chemotherapy, which was administered intravenously while he was an in-patient at hospital. Aggressive chemo, which kills fast-duplicating cancerous and healthy cells, is notorious for its terrible side-effects, such as hair loss and nausea. However, Grainger says he been lucky not to have suffered those ailments.

“My problem has been terrible itching. It’s been unbelievable, to be honest. It’s like you are crawling with insects.” He has also experienced loss of appetite.

Grainger’s fears that his days at Waseda International were numbered were confirmed in May — the same month he began chemotherapy — when he received a “notice of nonrenewal” letter from the company. This document outlines the reasons his employment at the school was terminated.

To quote: “A decision regarding any further contract renewal would be based on work attendance and the determination of Mr. Grainger’s performance of work duties. Based on the doctor’s certificate dated May 7, 2013 Mr. Grainger is unable to work from May 1 to the end of July.

“WIC [Waseda International Corp.] has therefore determined that Mr. Grainger is unable to satisfy attendance and work duty requirements detailed in the employment contract.”

In response to written questions, Waseda International said they are unable to talk to mass media about specific employees but were willing to give general comment about company policy.

Yukihisa Nakao, managing officer of the company’s language education department, said the decision to renew an employment contract or not is based on work performance and attendance, and “not on whether absences are due to an illness or other circumstances.”

“I would therefore like to stress that any belief that our company would terminate an employee’s contract due to illness is mistaken,” he says.

Mistaken or not, Japanese law does allow employers to terminate employees who are too ill to work.

“Management can legally fire someone if they are too sick to fulfill work duties,” says Louis Carlet, general secretary of the Zenkoku Ippan Tokyo General Union. “The law is cruel on this point.”

Carlet says the key issue for Grainger from a legal standpoint would be whether there was a “reasonable expectation” of contract renewal.

Carlet thinks Grainger would have a good chance of overturning the dismissal if he went to court.

Grainger would have to show that despite the six-month fixed-term contract he was placed on, he still had a reasonable expectation that it would be renewed, Carlet says.

This would be “because of the many one-year renewals” he had been given in the past, “because other teachers are usually renewed and because the renewal process is a formality. Court might take a couple years, but if he wins, he would get all back pay.”

Grainger would also have to convince the court that he did not miss enough days to constitute nonfulfillment of work duties, he adds.

Whether he has a case or not, the cold, hard reality for Grainger is that, as of Sept. 30, when his contract expired, he is not only extremely sick but also jobless, with little hope of future employment. And now, after undergoing 14 months of costly cancer treatment, he is struggling to make ends meet.

“All of a sudden, I was facing three operations in a month, plus a session of chemotherapy,” he says. “The money you just have to find from nowhere is horrendous.”

Although Grainger was enrolled in a private health insurance program through his job with Waseda International, that only covered 70 percent of his skyrocketing medical bills. “It works fine if you have to go in for a small operation, or you have a cold or something, but when you are in hospital every month over and over again, earning less, paying out more, it is a double whammy. Thirteen months of that has taken its toll. So, basically I am desperate for money — every month is a constant struggle.”

Grainger says he has received no additional support from Waseda International, such as offers to help out with outstanding hospital bills. He also says that management has shown a total lack of empathy with his situation. “They just don’t care. They haven’t visited me in hospital, or even sent flowers. They have never even asked me how I am.”

He stresses that although he feels very let down by the management at Waseda International, his fellow teachers at the school have supported him 100 percent.

Nakao from Waseda International says a health and safety committee is in place at the school to “promote the prevention of health problems and to maintain the health of employees.”

“Our company employs staff members who are responsible for personnel-related duties, and who are able deal with health — including mental health — concerns of employees at any time,” he explains. “With regards to any employee who is hospitalized due to a nonwork-related illness, it is not a common practice among Japanese companies to have a company representative visit the employee in hospital or to send flowers. Therefore, it is not fair to say that the company does not provide support to its employees just because these specific actions were not taken.”

Despite the huge series of challenges he has had to face, Grainger remains surprisingly upbeat. “I’ve got a really good support network here and some really good friends and everyone has been amazing and helped me out a lot,” he says. “Cancer has been like an affirmation of my friendships. It sorts the men out from the boys — you know who your friends are. I’ve never been a person who has been particularly comfortable asking for help from other people, and then suddenly I was in a position where I had to. I was overwhelmed.”

Good friends aside, there is no denying that Grainger is staring death in the face. “They have virtually told me my survival chances are zero. If you get malignant melanoma, you die of it. That isn’t to say you die of it the next day, or the next week, or even the next year. I would have been dead already if I hadn’t come to hospital when I did. I would have been dead before Christmas — 100 percent.”

Yet Grainger says he no longer lives every day in fear of dying. “I don’t really think about it like that anymore. Everything is a bonus.”

In fact, Grainger says, in many ways, his cancer has been life-affirming — even liberating.

“Having to face it and realize that you are a human being, a living creature, and whether you die sometime this year or sometime next year or in a few years’ time, or when you are supposed to die of old age, whenever that may be, you will eventually die.

“Everyone has to face it at some point in their life, and once you have done that psychologically, it is a freedom. It sets you free.”

Walk the line and support Grainger

On Saturday, Nov. 3, Neil Grainger and a group of his friends are planning to take a 40 km walk around the Yamanote Line in Tokyo.

The event is a fundraiser to help cover the mounting cost of Grainger’s medical expenses for his cancer treatment and to raise money for several cancer charities.

People can get involved by sponsoring one of the walkers or making a donation online.

A charity walk/run is also being held the day before the Yamathon, on Nov. 2, in Sandwell Valley in the English West Midlands.

For details of both events, go to http://www.yamathon.com Additional information about Grainger’s case and coping with illness in Japan can be found at http://www.supportneil.com and http://www.sickinjapan.com

| Hot Topics | |

|---|---|

Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

46 posts

• Page 1 of 2 • 1, 2

Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

http://www.japantimes.co.jp/community/2 ... ancer-hiv/

-

TennoChinko - Maezumo

- Posts: 1340

- Joined: Mon Feb 27, 2006 9:33 am

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

It would be better if his name was Dave Grainger because then the headline could be "Dave Grainger in Grave Danger". If it's any consolation to Neil and I'm sure it's not, Japanese companies fuck over their Japanese employees just as hard. Boggles my mind that an actual human being could do that to another human being. We need a "Humans are Cunts" thread.

- Mock Cockpit

- Maezumo

- Posts: 700

- Joined: Sun Mar 23, 2008 9:58 pm

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

Mock Cockpit wrote:It would be better if his name was Dave Grainger because then the headline could be "Dave Grainger in Grave Danger". If it's any consolation to Neil and I'm sure it's not, Japanese companies fuck over their Japanese employees just as hard. Boggles my mind that an actual human being could do that to another human being. We need a "Humans are Cunts" thread.

Sounds like America. While he is losing his job, he is required to get on NHS, which will be like 2000 yen a month since he has no job. He's not being totally thrown out on the street. THAT, would be America.

-

gaijinpunch - Maezumo

- Posts: 766

- Joined: Sat Nov 06, 2010 10:40 am

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

Corporashiunz are not 'h00man beingz'

-

Coligny - Posts: 21824

- Images: 10

- Joined: Sat Jan 17, 2009 8:12 pm

- Location: Mostly big mouth and bad ideas...

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

gaijinpunch wrote:Mock Cockpit wrote:It would be better if his name was Dave Grainger because then the headline could be "Dave Grainger in Grave Danger". If it's any consolation to Neil and I'm sure it's not, Japanese companies fuck over their Japanese employees just as hard. Boggles my mind that an actual human being could do that to another human being. We need a "Humans are Cunts" thread.

Sounds like America. While he is losing his job, he is required to get on NHS, which will be like 2000 yen a month since he has no job. He's not being totally thrown out on the street. THAT, would be America.

If he's on a work visa, what happens once that expires?

BTW, your insurance rates are based on previous year's income so they can be pretty high for your first year of unemployment.

-

Samurai_Jerk - Maezumo

- Posts: 14387

- Joined: Mon Feb 09, 2004 7:11 am

- Location: Tokyo

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

He should have got himself an interglobal health policy... he would have been covered in full except the HIV.

-

IparryU - Maezumo

- Posts: 4285

- Joined: Thu Jun 04, 2009 11:09 pm

- Location: Balls deep draining out

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

This story just reminded me of a similar story I came across in Korea last month. They had a sign with the story and a donation box set up at a bar he used to hang out at. Apparently after he got sick his hagwon fired him which mean he lost his health insurance too. Now that he's back in America he might be even more fucked though.

-

Samurai_Jerk - Maezumo

- Posts: 14387

- Joined: Mon Feb 09, 2004 7:11 am

- Location: Tokyo

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

gaijinpunch wrote:Mock Cockpit wrote:It would be better if his name was Dave Grainger because then the headline could be "Dave Grainger in Grave Danger". If it's any consolation to Neil and I'm sure it's not, Japanese companies fuck over their Japanese employees just as hard. Boggles my mind that an actual human being could do that to another human being. We need a "Humans are Cunts" thread.

Sounds like America. While he is losing his job, he is required to get on NHS, which will be like 2000 yen a month since he has no job. He's not being totally thrown out on the street. THAT, would be America.

I really don't see how Waseda IC fucked him. They didn't give him HIV or cancer and it sounds like he was just on contract work, not a regular employee. I feel bad for the guy but it sounds like he isn't capable of doing the work he was under contract for so I find it hard to hate on Waseda IC for not wanting to renew his contract. (or hold them responsible for accommodating him just to keep him employed) Isn't this more of a welfare/unemployment issue?

-

matsuki - Posts: 16047

- Joined: Wed Feb 02, 2011 4:29 pm

- Location: All Aisu deserves a good bukkake

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

chokonen888 wrote:gaijinpunch wrote:Mock Cockpit wrote:It would be better if his name was Dave Grainger because then the headline could be "Dave Grainger in Grave Danger". If it's any consolation to Neil and I'm sure it's not, Japanese companies fuck over their Japanese employees just as hard. Boggles my mind that an actual human being could do that to another human being. We need a "Humans are Cunts" thread.

Sounds like America. While he is losing his job, he is required to get on NHS, which will be like 2000 yen a month since he has no job. He's not being totally thrown out on the street. THAT, would be America.

I really don't see how Waseda IC fucked him. They didn't give him HIV or cancer and it sounds like he was just on contract work, not a regular employee. I feel bad for the guy but it sounds like he isn't capable of doing the work he was under contract for so I find it hard to hate on Waseda IC for not wanting to renew his contract. (or hold them responsible for accommodating him just to keep him employed) Isn't this more of a welfare/unemployment issue?

Do you feel they have more of an obligation to keep someone of if they're a permanent employee?

-

Samurai_Jerk - Maezumo

- Posts: 14387

- Joined: Mon Feb 09, 2004 7:11 am

- Location: Tokyo

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

IparryU wrote:He should have got himself an interglobal health policy... he would have been covered in full except the HIV.

Interglobal used to have relatively low lifetime payout limits on their policies, I'm not sure if they still do. If this is the case he would have hit that limit long ago and then been totally SOL. In order to get real insurance again he would have to pay 1mil yen in back premium payments.

And you run and you run to catch up with the sun but it's sinking

Racing around to come up behind you again

The sun is the same in a relative way, but you're older

Shorter of breath and one day closer to death

Racing around to come up behind you again

The sun is the same in a relative way, but you're older

Shorter of breath and one day closer to death

-

FG Lurker - Posts: 7855

- Joined: Mon Nov 29, 2004 6:16 pm

- Location: On the run

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

Samurai_Jerk wrote:chokonen888 wrote:gaijinpunch wrote:Mock Cockpit wrote:It would be better if his name was Dave Grainger because then the headline could be "Dave Grainger in Grave Danger". If it's any consolation to Neil and I'm sure it's not, Japanese companies fuck over their Japanese employees just as hard. Boggles my mind that an actual human being could do that to another human being. We need a "Humans are Cunts" thread.

Sounds like America. While he is losing his job, he is required to get on NHS, which will be like 2000 yen a month since he has no job. He's not being totally thrown out on the street. THAT, would be America.

I really don't see how Waseda IC fucked him. They didn't give him HIV or cancer and it sounds like he was just on contract work, not a regular employee. I feel bad for the guy but it sounds like he isn't capable of doing the work he was under contract for so I find it hard to hate on Waseda IC for not wanting to renew his contract. (or hold them responsible for accommodating him just to keep him employed) Isn't this more of a welfare/unemployment issue?

Do you feel they have more of an obligation to keep someone of if they're a permanent employee?

Legally, no....but say, if it was my company and the dude was with me from the start, I'd definitely morally feel obligated to try and accommodate him. Whether that's feasible or not, is another question. It sounds like they tried and basically found it wasn't workable. Sucks but so be it...but that's where I'd imagine unemployment/welfare to take over. I just don't like the idea of placing the burden/responsibility on the employer. If you take it a step further, cancer is one thing but unless he was born with it, you also have to consider how he got HIV. Dirty blood transfusion? Doctor/clinic/etc. liable. Evil ex gf? Pretty sure she can be held liable. Banging Thai hookers bareback? Personal responsibility...

-

matsuki - Posts: 16047

- Joined: Wed Feb 02, 2011 4:29 pm

- Location: All Aisu deserves a good bukkake

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

chokonen888 wrote:I really don't see how Waseda IC fucked him. They didn't give him HIV or cancer and it sounds like he was just on contract work, not a regular employee. I feel bad for the guy but it sounds like he isn't capable of doing the work he was under contract for so I find it hard to hate on Waseda IC for not wanting to renew his contract. (or hold them responsible for accommodating him just to keep him employed) Isn't this more of a welfare/unemployment issue?

There are two sides to this.

Yes, you're correct that as a contracted employee they can refuse to renew his contract and thus he has no job.

However the question then becomes, "If he had been Japanese would he have been a contracted employee or a permanent employee?" Many universities keep gaijin on very short-term contracts so they are disposable rather than make them permanent employees like they would with Japanese doing the same job.

And you run and you run to catch up with the sun but it's sinking

Racing around to come up behind you again

The sun is the same in a relative way, but you're older

Shorter of breath and one day closer to death

Racing around to come up behind you again

The sun is the same in a relative way, but you're older

Shorter of breath and one day closer to death

-

FG Lurker - Posts: 7855

- Joined: Mon Nov 29, 2004 6:16 pm

- Location: On the run

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

FG Lurker wrote:IparryU wrote:He should have got himself an interglobal health policy... he would have been covered in full except the HIV.

Interglobal used to have relatively low lifetime payout limits on their policies, I'm not sure if they still do. If this is the case he would have hit that limit long ago and then been totally SOL. In order to get real insurance again he would have to pay 1mil yen in back premium payments.

1.5M is for the cheepest shit... but his national would cover a chunk of it and the private healthcare would cover the rest. Still fuck of a lot better than having to cover the remainder of all those bills without any help...

but back to the issue... they are trying to huss and fuss over him losing his job. the guy still has national health care. so they are not stripping him of that and leaving him to die. the employer is doing a reasonable thing... the guy cannot work. if someone cannot work, then they get cut.

shitty to say, but the guy does not have much left and the government is paying hella money to keep him around for an extra year or two.

-

IparryU - Maezumo

- Posts: 4285

- Joined: Thu Jun 04, 2009 11:09 pm

- Location: Balls deep draining out

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

FG Lurker wrote:chokonen888 wrote:I really don't see how Waseda IC fucked him. They didn't give him HIV or cancer and it sounds like he was just on contract work, not a regular employee. I feel bad for the guy but it sounds like he isn't capable of doing the work he was under contract for so I find it hard to hate on Waseda IC for not wanting to renew his contract. (or hold them responsible for accommodating him just to keep him employed) Isn't this more of a welfare/unemployment issue?

There are two sides to this.

Yes, you're correct that as a contracted employee they can refuse to renew his contract and thus he has no job.

However the question then becomes, "If he had been Japanese would he have been a contracted employee or a permanent employee?" Many universities keep gaijin on very short-term contracts so they are disposable rather than make them permanent employees like they would with Japanese doing the same job.

If that's the point they're trying to argue, I'm all for it....but that's a discrimination issue that needs to be addressed based on if the company indeed treats their foreign employees differently.

-

matsuki - Posts: 16047

- Joined: Wed Feb 02, 2011 4:29 pm

- Location: All Aisu deserves a good bukkake

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

chokonen888 wrote:If you take it a step further, cancer is one thing but unless he was born with it, you also have to consider how he got HIV. Dirty blood transfusion? Doctor/clinic/etc. liable. Evil ex gf? Pretty sure she can be held liable. Banging Thai hookers bareback? Personal responsibility...

You seems to be implying that his employer should dig into his private life and decide whether or not to keep him on the payroll based on how he contracted HIV. Interesting. Anyway, HIV is apparently not the issue here. That's not what's preventing him from working.

-

Samurai_Jerk - Maezumo

- Posts: 14387

- Joined: Mon Feb 09, 2004 7:11 am

- Location: Tokyo

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

Samurai_Jerk wrote:chokonen888 wrote:If you take it a step further, cancer is one thing but unless he was born with it, you also have to consider how he got HIV. Dirty blood transfusion? Doctor/clinic/etc. liable. Evil ex gf? Pretty sure she can be held liable. Banging Thai hookers bareback? Personal responsibility...

You seems to be implying that his employer should dig into his private life and decide whether or not to keep him on the payroll based on how he contracted HIV. Interesting. Anyway, HIV is apparently not the issue here. That's not what's preventing him from working.

As I said, it's a step further, not necessarily from an employers POV...not saying they should base his employment on that if it's not what's preventing him from working.

While we're on that tangent though...

Say the guy knew he had HIV, gets this job and hides it until he no longer can. Do you think the employer should be responsible for keeping him on the payroll? What if he had HIV when he got the job and just didn't know, does that change your answer? Do you think it's ok if employees test prospective employees for HIV before hiring?

-

matsuki - Posts: 16047

- Joined: Wed Feb 02, 2011 4:29 pm

- Location: All Aisu deserves a good bukkake

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

chokonen888 wrote:While we're on that tangent though...

Say the guy knew he had HIV, gets this job and hides it until he no longer can. Do you think the employer should be responsible for keeping him on the payroll? What if he had HIV when he got the job and just didn't know, does that change your answer? Do you think it's ok if employees test prospective employees for HIV before hiring?

WTF? Is it 1985?

-

Samurai_Jerk - Maezumo

- Posts: 14387

- Joined: Mon Feb 09, 2004 7:11 am

- Location: Tokyo

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

My point is that one's health isn't and shouldn't be the responsibility of your employer.

-

matsuki - Posts: 16047

- Joined: Wed Feb 02, 2011 4:29 pm

- Location: All Aisu deserves a good bukkake

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

chokonen888 wrote:My point is that one's health isn't and shouldn't be the responsibility of your employer.

It also shouldn't be their business unless you have a disability or illness that prevents you from doing the job you're hired for. People who are HIV positive can live normally for decades with the right treatment.

-

Samurai_Jerk - Maezumo

- Posts: 14387

- Joined: Mon Feb 09, 2004 7:11 am

- Location: Tokyo

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

Samurai_Jerk wrote:chokonen888 wrote:My point is that one's health isn't and shouldn't be the responsibility of your employer.

It also shouldn't be their business unless you have a disability or illness that prevents you from doing the job you're hired for.

Totally agree

Samurai_Jerk wrote:People who are HIV positive can live normally for decades with the right treatment.

I know, I should have said cancer as HIV isn't the best example.

-

matsuki - Posts: 16047

- Joined: Wed Feb 02, 2011 4:29 pm

- Location: All Aisu deserves a good bukkake

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

Samurai_Jerk wrote:chokonen888 wrote:My point is that one's health isn't and shouldn't be the responsibility of your employer.

It also shouldn't be their business unless you have a disability or illness that prevents you from doing the job you're hired for. People who are HIV positive can live normally for decades with the right treatment.

Thank you!! Agree x 1m.

These days, living with HIV is akin to living with diabetes.

The guy in the original story sounds pretty fucked all around.

GomiGirl

The Keitai Goddess!!!

The Keitai Goddess!!!

-

GomiGirl - Posts: 9129

- Joined: Fri Jul 05, 2002 3:56 pm

- Location: Roamin' with my fave 12"!!

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

BTW, your insurance rates are based on previous year's income so they can be pretty high for your first year of unemployment.

It's not the gospel, but I believe you can go in and say, "look this is what I make now, sorry" and they will adjust. Talked about this w/ my tax guy when I had to figure out some options.

-

gaijinpunch - Maezumo

- Posts: 766

- Joined: Sat Nov 06, 2010 10:40 am

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

gaijinpunch wrote:BTW, your insurance rates are based on previous year's income so they can be pretty high for your first year of unemployment.

It's not the gospel, but I believe you can go in and say, "look this is what I make now, sorry" and they will adjust. Talked about this w/ my tax guy when I had to figure out some options.

That shit didn't work for me when I was unemployed. I guess they figured I was making too much between Hello Work and my 'baito.

-

Samurai_Jerk - Maezumo

- Posts: 14387

- Joined: Mon Feb 09, 2004 7:11 am

- Location: Tokyo

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

Samurai_Jerk wrote:

Do you feel they have more of an obligation to keep someone of if they're a permanent employee?

Employment conditions in Japan are a popularity contest, and gaijin aren't popular.

-

legion - Maezumo

- Posts: 2681

- Joined: Thu Dec 09, 2010 11:30 pm

- Location: Tokyo

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

What happens in the case of kokuminkenkohoken if someone has to be hospitalised and isn't able to work/loses their job?

-

MrUltimateGaijin - Maezumo

- Posts: 339

- Images: 4

- Joined: Sat Jan 22, 2005 9:52 pm

- Location: Yokohama

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

MrUltimateGaijin wrote:What happens in the case of kokuminkenkohoken if someone has to be hospitalised and isn't able to work/loses their job?

I may be totally wrong but I believe the company is required to give them a job when they can work again but the law does not say what job. Many J-girls that leave to have babies come back to work only to find their "time served" has been reset to 0 and their salary to what ever the noobs get which is why most don't go back.

-

wuchan - Posts: 2015

- Joined: Tue Jun 17, 2008 11:19 pm

- Location: tied to a chair in a closet at the local koban

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

wuchan wrote:MrUltimateGaijin wrote:What happens in the case of kokuminkenkohoken if someone has to be hospitalised and isn't able to work/loses their job?

I may be totally wrong but I believe the company is required to give them a job when they can work again but the law does not say what job. Many J-girls that leave to have babies come back to work only to find their "time served" has been reset to 0 and their salary to what ever the noobs get which is why most don't go back.

If a person is hospitalized and can't work or loses their job, what happens when they can no longer make their hoken payments? I could be wrong but i think national health insurance covers that situation.

-

MrUltimateGaijin - Maezumo

- Posts: 339

- Images: 4

- Joined: Sat Jan 22, 2005 9:52 pm

- Location: Yokohama

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

MrUltimateGaijin wrote:wuchan wrote:MrUltimateGaijin wrote:What happens in the case of kokuminkenkohoken if someone has to be hospitalised and isn't able to work/loses their job?

I may be totally wrong but I believe the company is required to give them a job when they can work again but the law does not say what job. Many J-girls that leave to have babies come back to work only to find their "time served" has been reset to 0 and their salary to what ever the noobs get which is why most don't go back.

If a person is hospitalized and can't work or loses their job, what happens when they can no longer make their hoken payments? I could be wrong but i think national health insurance covers that situation.

In that situation I believe the company hoken runs until the end of the tax year than national kicks in. National is based on earnings but they don't calculate until you are on national for one full year. So, if you make nothing, they charge nothing (in theory). There is a shit ton of paperwork and you will get hoken bills for a few years but for some reason they issue new cards every year even if you are not up to date.

I live in an inaka town far from the 23 wards, things out here may be different.

-

wuchan - Posts: 2015

- Joined: Tue Jun 17, 2008 11:19 pm

- Location: tied to a chair in a closet at the local koban

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

MrUltimateGaijin wrote:What happens in the case of kokuminkenkohoken if someone has to be hospitalised and isn't able to work/loses their job?

The laws are pro-worker (not pro-company) but I don't think someone under short-term contract is considered a worker. I was on the chopping block at a large bank one year, and they always opt to douse you with money to avoid lawsuit. Was kind of nice.

what happens when they can no longer make their hoken payments?

Whatever the book says to a T. I had an NHS issue and was told one thing, and when I went to execute that plan they didn't know how to handle it, so they busted out the manual and it was set in stone. The truth is nobody really knows until that exact scenario happens. I was not happy.

-

gaijinpunch - Maezumo

- Posts: 766

- Joined: Sat Nov 06, 2010 10:40 am

Re: Waseda University International Corp Fucks Fucked Gaijin

Samurai_Jerk wrote:chokonen888 wrote:While we're on that tangent though...

Say the guy knew he had HIV, gets this job and hides it until he no longer can. Do you think the employer should be responsible for keeping him on the payroll? What if he had HIV when he got the job and just didn't know, does that change your answer? Do you think it's ok if employees test prospective employees for HIV before hiring?

WTF? Is it 1985?

It is in Korea where foreign English teachers have to take an HIV and drugs test (and chest x ray) to get their version of the gaijin card as well as when renewing their visa or changing jobs in some cases. The hospitals also slip in other tests that Korean Immigration doesn't require, like tests for STDs.

Yet imported sex workers on 'entertainer' visas do not have take these tests. That tells you a lot about Korean society's priorities even if you haven't lived there in that brothel on every street culture - that is hardly an exaggeration. I understand Korean society doesn't want to deal with the financial burden of foreigners with HIV but it really is more to do with the discriminatory attitude that HIV comes from foreigners.

It's more comfortable for the Koreans to have that attitude because then they do not have to deal openly with their culture of husbands going out routinely with the company on sex parties after the week has finished (most Koreans are married, it's a social obligation still enforced by attitudes), or with acknowledging that it's odd for a first world country to have brothels next door to a kindergarten or elementary school and for younger prostitutes to be openly picked up by the pimp in usual apartments in a society that boasts of its family values, ferried to their work place and dropped back all hours of the morning. The sex trade is in plain sight and just about everywhere but continually denied to exist.

Many young Korean males still have their first sexual experience with a prostitute (when they're not horsing around with other males but for males who prioritise each other over females they are really homophobic in that country) and honest Korean medical workers will admit that STD rates are unusually high among Korean wives because of the sexual norms of the society. Koreans are incredibly closed to even discussing these things and it comes out with the paranoia directed against foreign English teachers, for example.

What is happening to the teacher at Waseda here pales somewhat by contrast to the fact that the Korean authorities have the minority of English teachers who test HIV positive for their employment health checks sacked from their jobs and deported very quickly. The 2nd to last year I was in Korea a few young gay British male teachers had positive HIV tests and were deported within a week.

- wangta

- Maezumo

- Posts: 475

- Joined: Sat Jan 26, 2013 5:33 pm

46 posts

• Page 1 of 2 • 1, 2

Who is online

Users browsing this forum: Baidu [Spider] and 8 guests